History

Fowler History and a scandal

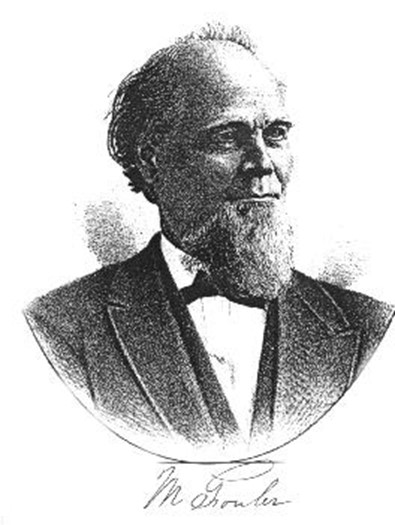

Moses Fowler (1815-1889) was born on a farm near Circleville, Ohio. His father was a veteran of the Revolutionary War and a Virginian by birth. Moses remained on the farm until 16 then apprenticed as a tanner. He impressed his employer so much that he was offered a partnership after just two years as an apprentice, but Moses declined. Instead he accepted a clerkship at a mercantile store in Adelphia. In 1839 he moved to Lafayette with John Purdue, who would go on to found Purdue University, and they formed a partnership in the dry goods business. He had amassed a total of $700 to start this new venture.

After five years Moses and John Purdue amicably parted ways and Moses formed his own dry goods business. He then partnered with W. F. Reynolds and Robert Stockwell to expand into the wholesale grocery and goods business supplying other stores. Through this time Moses had under contract a fleet of steamships bringing goods up and down the Wabash River to the Mississippi as far south as New Orleans and east over the Erie Canal through the Great Lakes and beyond. Frequently 6 to 8 of his ships at a time were seen docked at the Lafayette Port. Lafayette being the navigable head of the Wabash River and terminus to the Erie Canal poised Moses and Lafayette for great success.

Two years after his arrival in Lafayette, Moses was asked to be a director of the old Indiana State Bank. He used this opportunity to learn the banking industry and after he and his partners wound up the wholesale goods business Moses moved into banking full time. With the organization of The Bank of the State, Moses was selected to build a Lafayette branch with $300,000 in capital. He was quickly made president of that bank, and later supervisor of all branches in the area. Throughout the eight years of the bank’s charter Moses made it with the exception of one year the strongest branch in the state system.

In 1865 Moses sought and secured a charter for the National State Bank of Lafayette with $600,000 in capital. It was an even greater success, and once it’s charter expired in 1885 Moses had intended to retire. But due to pressure from his friends and former business partners Moses was convinced to build a third bank, called the Fowler National Bank of Lafayette. This bank he capitalized primarily himself with $100,000. Because of his reputation and experience deposits at this new bank quickly exceeded $1,000,000, a very large sum for the day. In fact this number exceeded the sum of all other banks combined operating in the area.

His other ventures in this time period included building the Cincinnati, Lafayette, and Chicago railroad and the second largest slaughterhouse in the country located in Chicago, conveniently near the head of his railroad. Moses also helped form the town of Fowler, and donated the land and $40,000 to build a courthouse and city facilities to establish the county seat which moved from Oxford. At the height of his holdings Moses owned over 25,000 acres of farmland primarily in Benton County. He had up to 10,000 acres planted and another 10,000 acres grazed by cattle.

During this time Moses met his beloved wife, Eliza Hawkins, and married her in 1844. She was the sister of the wife of Adams Earl, another prominent Lafayette businessman and frequent partner with Moses in his land and farming ventures. The Fowlers enjoyed traveling, and during his travels in New York Fowler's imagination was struck by a Gothic Revival home he had visited. He built his dream home based on similar plans by renowned designer A.J. Downing, acting as his own architect.

Fowler broke ground on his dream in 1851, only 12 years after starting his first business in Lafayette, and saw it completed in 1852. The mansion stands on a hill which allowed the Fowlers to watch a then young Lafayette grow into the thriving city it is today. The railroad he would later bring to town also ran by the mansion, and it’s said that Moses would frequently sit on his porch in the evenings to ensure the conductors ran on time.

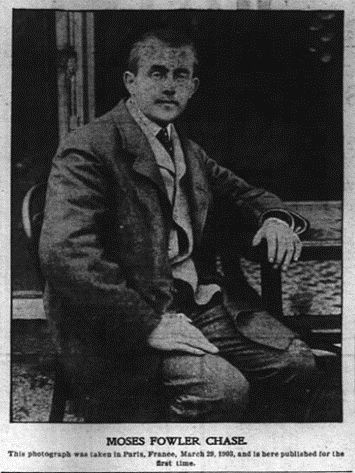

Moses and Eliza had five children, two of which died in infancy. Their surviving children were James, Annis and Ophelia. Annis passed in 1885, six years after having a son with her husband Fred Chase, a respected lawyer. This son was named Moses Fowler Chase.

Moses’ son James went to Purdue then fought in the Civil War. After his return he followed Moses into the banking industry and continued to run the Fowler National Bank after Moses passed. Ophelia married Charles H. Duhme, a jeweler from Cincinnati.

At the time of his death, Moses Fowler was one of the wealthiest men in the midwest, having amassed a fortune of over 3 million dollars, which is roughly 90 million adjusted for inflation. A biography written just after his death notes that he led a professional career of uncommon integrity, in which he was only sued twice, and won both cases.

A legal battle ensued over the estate, as Moses and his wife Eliza had been estranged for the last 10 years of Moses’ life and had agreed to live apart but not divorce. They had a very bitter relationship, one story recounts that Moses had come by the house and stooped to pick up something near a window, and Eliza poured a teapot of scalding water out the window onto him.

It took several years to resolve the conflict and a settlement was finally agreed to that significantly changed Moses' original wishes. In fact we have many of the original court documents, witness interview transcripts, and statements from this case at the Fowler Mansion. We have read news reports that this conflict was also due to a stipulation Moses had imposed that none of the land in Benton county could be sold for 25 years. However that is not noted in the legal documents recently discovered. Eliza did get an appropriate inheritance (at the time a wife did not automatically share her husband’s assets), and Moses Fowler Chase became a millionaire as a young child. He was called in the papers “The richest baby in Indiana.”

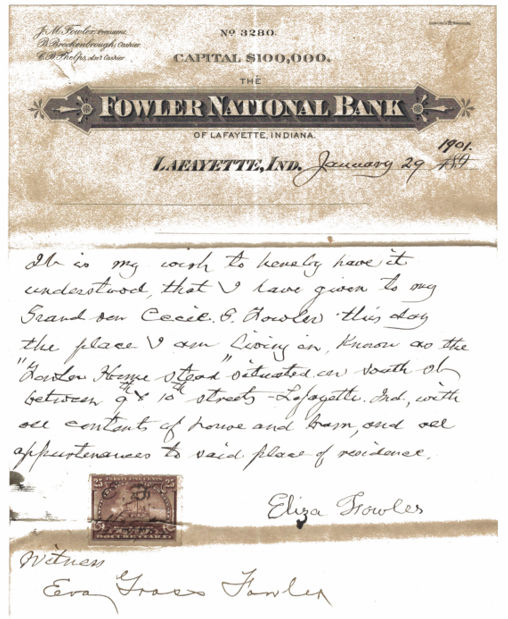

This outcome greatly concerned Eliza, and she believed her will would be similarly contested as she was estranged from her daughter Ophelia due to her disapproval of Ophelia’s “playboy” lifestyle. Eliza substantially cut Ophelia out of her will, and signed over before her death most of her assets to her son James, and grandsons including Moses Fowler Chase and James’ sons. Cecil Fowler was James Fowler’s oldest surviving son and he was granted the Fowler House Mansion and contents. In fact we possess the note and tax stamp that Eliza used to grant the home to Cecil. This grant thankfully was later upheld, which was instrumental in the Fowler House Mansion being maintained and renovated. Had Ophelia obtained the house it’s likely she would have sold it as she resided in Cincinnati with no positive ties to Lafayette, and it’s preservation would have been far less certain.

After his mother’s passing, Chase’s father Fred appeared to have little interest in caring for him while running his successful law practice. Fred allowed the young boy to spend most of his youth in Cincinnati with his Aunt Ophelia, though Chase was mostly ignored by Ophelia and her husband, that is until Chase became very wealthy.

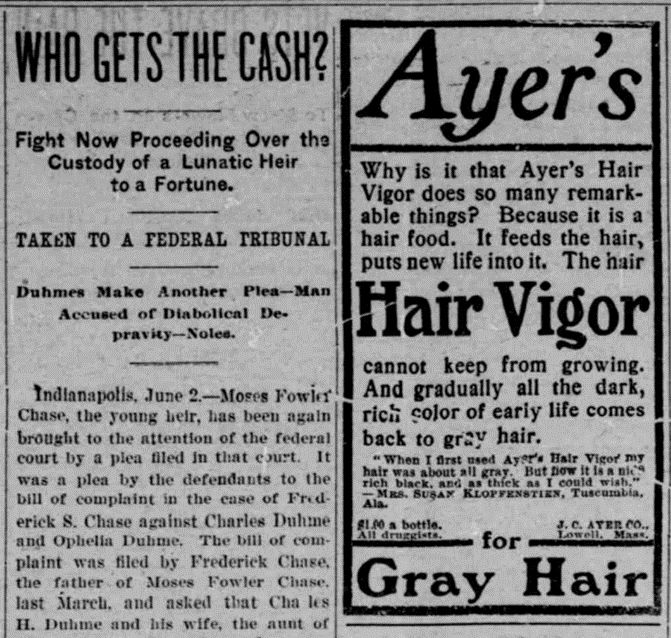

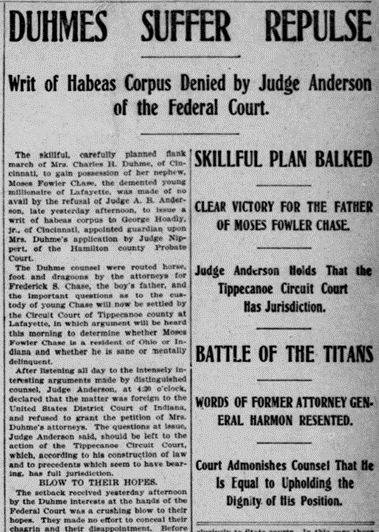

Once Moses passed, Ophelia used Chase’s portion of her father’s inheritance to care for him, and herself, in luxurious style. He attended the best boarding schools and then Yale. Upon coming of age he was returned to Cincinnati and brought before a board of physicians by Ophelia to be declared mentally fit to manage his own affairs, which the board of doctors affirmed. This was perhaps a way for Ophelia to separate Chase from the presumed guardianship of his father as he was now of age and his mental fitness was coming into doubt. Chase’s father learned of this and had him brought to Lafayette as he apparently also had doubt as to his son’s mental fitness. After a short visit Chase was sent back to Cincinnati without his father seeking to retain guardianship. But something must have happened shortly after his return to Cincinnati which caused Chase’s father and doctors to agree he should be committed. His father brought Chase to the Sanitarium at Flint Michigan to be evaluated. He was officially declared insane.

Chase and his father Fred were returning from Flint to allow Chase to be cared for locally in Lafayette. In Detroit they were intercepted by Ophelia and her husband Charles Duhme at the train station. While Ophelia distracted Fred at a local hotel with an argument, her husband Charles lured Chase to a waiting carriage and fled to New York, followed shortly by Ophelia. One article recounts that when Fred realized the deception he confronted Ophelia, who laughed in his face and left.

Being a well respected lawyer, Fred immediately went to Lansing to secure requisition papers from the Governor of New York to have his son returned before he could leave the country. But he was unfortunately unable to fully prove he was being kidnapped, as he had been in the care of Ophelia many of the last years. The papers described the incident as “the youthful millionaire with a fast-waning mind was being abducted from his own father.”

Fred followed them to New York, only to find they had booked passage and left on a steamer to France. Ophelia of course refused to disclose Chase’s whereabouts to the court or to his father to prevent him being examined and ruled incompetent and thus overturning her asserted guardianship. Fred spent a great deal of money with the Pinkerton Agency and others to scour France and Paris in particular.

Ophelia had access to some of Chase’s existing fortune and spent a great deal of it during and on the protracted legal battle. Ophelia and Charles had taken Chase to a private sanitarium outside Paris and committed him under a fake name.

At home, Eliza passed in 1902. Among the charitable donations upon her death, Eliza gave $70,000 to Purdue to erect Eliza Fowler Hall. She was rumored to have said, referring to her husband’s cemetery monument in Battleground she found gaudy, “I will make that monument of Moses Fowler’s to look cheap. I want something erected to my memory that will make people remember the name.” Thus was erected Eliza Fowler Hall. Not Fowler hall, she was very clear in a letter to the Purdue trustees, Eliza Fowler Hall. Her son James later donated over $40,000 to install an organ and other finishing touches. The hall has since been razed, but Eliza’s name persists on a wing of the replacement building.

As expected her passing kicked off a very bitter inheritance battle. Although she had already given away most of her assets, a sizable portion of which belonged to Chase, or to his guardian at least. Ophelia of course objected to receiving nothing, as she had already spent her inheritance from her father as well as what she could access from Chase's. She again tried to legally assert her guardianship of Chase as she had overseen his youth and school years.

It had been three years now since Chase had disappeared. One of the detectives Fred had employed for these years in Paris had a lead, and located Chase in a private Asylum outside of Paris. He returned to Paris to amass a force of other detectives to assist in his abduction, but overnight Chase was spirited away, and the trail went cold.

Months later the same detective found Chase had been moved back to an institution only three miles from the first. Not wanting to risk him disappearing again, the detective immediately confronted the owner of the institution’s wife, and she eventually admitted that she was caring for a Moses Fowler Brown, but she knew he was Chase.

Her husband entered the room and denied this, but eventually yielded that in order to not violate his word he would bring all the patients before the detective. If he could identify Chase the doctor would not deny it, thus not violating his word to Ophelia and Charles. Chase was of course identified, but they would not permit him to leave the institution. The detective sent word to Fred Chase, and he immediately sent a lawyer to act on his behalf to gain the support of the State Department and French Consul-General. The French Consul-General was granted temporary guardianship and took possession of Chase days later intending to secure him until he could turn him over to his father’s representative.

Upon hearing of this Charles and Ophelia booked passage to Europe from New York as well, and dispatched their own detectives and lawyers to attempt to intercept and abduct Chase before he got on the steamer home. The attorney representing Fred was able to get Chase aboard the ship under cover of darkness, evading Ophelia’s lawyers and detectives. This situation was conveyed by telegram to Ophelia and they did not embark on their journey to Europe, instead staying to attempt to secure Chase upon his arrival in New York or Lafayette. Many national papers incorrectly reported that they had embarked and would have passed Chase at sea.

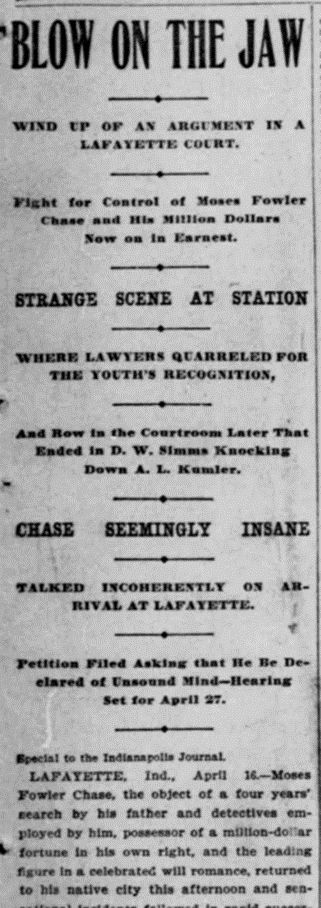

Fred was in New York to meet his son, and paid a tug operator to bring him out to the steamer before it docked in order to see Chase. Fred was first aboard climbing a rope ladder to see his son. One witness said Fred aged 10 years after seeing his son’s mental and physical state. Chase was completely incoherent, drooling, and emaciated, unaware of his surroundings. Fred’s heart was broken, he had tried belatedly to reconnect with his son in the previous years, but it was too late. One paper wrote a witness’s statement of the encounter on the ship, “He buried his son’s head on his shoulder and wept, his son never recognizing him.”

They were able to disembark uneventfully and went straight to a private train car to Lafayette. Two days later Chase, Fred, his attorney and guards arrived in Lafayette. Police were there to maintain order as a significant crowd had gathered. As Fred and his attorney held Chase tightly to get him from the train, an attempt was made to wrestle Chase free once again by Ophelia’s lawyers and detectives. They were repelled by the police and Fred’s detectives, though it was a significant physical fight in the street in front of the Lahr Hotel. Chase was eventually put in a waiting carriage and sped down the street to the offices of Fred’s lawyer Simms, where the doors were barricaded and armed private detectives stationed around the block.

Chase was eventually moved to safer quarters taking over an entire floor of the St Elizabeth Hospital (of which Eliza had been a significant financial supporter) where he could receive care under private and police guard until the trial would resume. Stories say that the bells usually reserved for fire emergencies were used as the signal of any attack, bringing all the guards and police to defensive positions if they were rung.

Transcripts of Chase’s examinations by court appointed doctors show he was at this time barely cognizant of who he was or where he was, and had no understanding of the court case of which he was the center, nor that he possessed $1.5 million in addition to this next inheritance, making him one of the wealthiest men in the Midwest.

This entire conflict had been in the national and European press throughout, both for the amount of money involved in the inheritance, and the prominence of the family. Ophelia’s claim of guardianship was contested by James and Fred to the Indiana Supreme Court and overturned. Other parts of the case ended up in Federal court and eventually Ophelia’s claims over Chase were struck down. The US Supreme Court declined to hear her appeals. This allowed the inheritance to be distributed primarily under James Fowler’s direction as Eliza had intended, though there were other conflicts to be resolved. Overall a settlement was agreed to, which was not exactly Eliza’s wishes, but gave Ophelia some share and ended the conflict while leaving Chase back in his father’s care.

Ophelia lived out her days relatively quietly in Cincinnati. In 1925 she gifted a tract of land she had inherited to Purdue University, the proceeds of which were used to build the Ophelia Duhme Residence hall for Women. The hall still stands today, and has been home to many distinguished women, including Amelia Earhart. Ironically, Ophelia’s own will was also contested after her death, as she had made out several documents over time that contradict one another. Her brother James and her cousin Cecil Fowler filed suit to protect her estate arguing that her last wills were given when she was sick and of unsound mind. These would have given significant amounts of money to several friends she’d met late in life and a small church in Canada. It’s unclear how this was resolved. It’s also not clear if James and Cecil had mended their relationship with Ophelia prior to her passing, but their defense of her estate implies they may have reconciled.

Chase never gained mental competency, but was well cared for by all accounts. After his father Fred’s passing his cousin Cecil Fowler, then resident of the Fowler House Mansion, was appointed his guardian and oversaw his affairs honorably until Chase’s death.

James Fowler continued as a very successful and respected banker in Lafayette. Cecil Fowler and others in the family invested heavily in the Miami area helping drain swamp land and building the first major hotel in the area, The Flamingo. That building has been replaced but the Fowler influence lives on. Their interests in Florida and Texas are what we’re told drew the family away from town, and resulted in the Fowler House Mansion leaving the family.

Renovations & Continued Use

Throughout the years, the Fowler House Mansion has been renovated and updated to keep pace with the modern world. In 1916-1917, Cecil and his wife Louise, began extravagant renovations of the mansion. These renovations included adding an English Tudor-style dining room, a garden room that doubled as a living room, an Italian-style patio and gardens, complete with terraced steps, fountains, a tea house and reflecting pool, indoor plumbing, electricity, as well as servants quarters and an indoor kitchen.

The upstairs of the mansion houses seven bedrooms and five bathrooms, including a full attic, which served as a playroom and gymnasium for the Fowler children. The Fowlers lived in grand style, traveled extensively, and loved to host elaborate parties. Like many during the period, Prohibition did not slow them down one bit, and their parties were somewhat legendary. One of the attic rooms crawl spaces served as the storage area for alcohol during that period. Their eldest son even operated a "speakeasy" complete with a game room in the basement called the "Crock Club." This was a frequent hangout spot for his friends and fellow Purdue students. Fifty cents bought you all the beer you could drink and "Shorty" (the gardener) served up hamburgers for a nickel each.

Passing on the Fowler Legacy

By 1941, Cecil and Louise's children were grown, and the couple wished to downsize. They made the difficult decision to relinquish the mansion. After almost 90 years in the Fowler family, the house was sold to the Tippecanoe County Historical Association. The house became the home for the Association's offices, collections, and served as the County Museum. Following an extended period of marked decline in visitation, the Association closed the museum in 2005, although it was still partially used for offices, storage, and rented out for weddings and other events.

In 2014, the TCHA decided that running the Fowler House Mansion as a venue for special events required a specialized staff, and they sought a new, modern location to house their offices. Understanding the importance of the property, they sold it to the 1852 Foundation who preserve its legacy to this day.

The 1852 Foundation is a 501(c)3 non-profit whose mission is to preserve the Mansion. Matt Jonkman invested over $2 million in the foundation to renovate and update the Fowler House Mansion, including a full commercial kitchen. All proceeds from rentals and catering go directly to preserving the house. The long term goal of the foundation is to support the house completely on rental and catering revenue, thus preserving it for the long term. We appreciate your support in this goal!